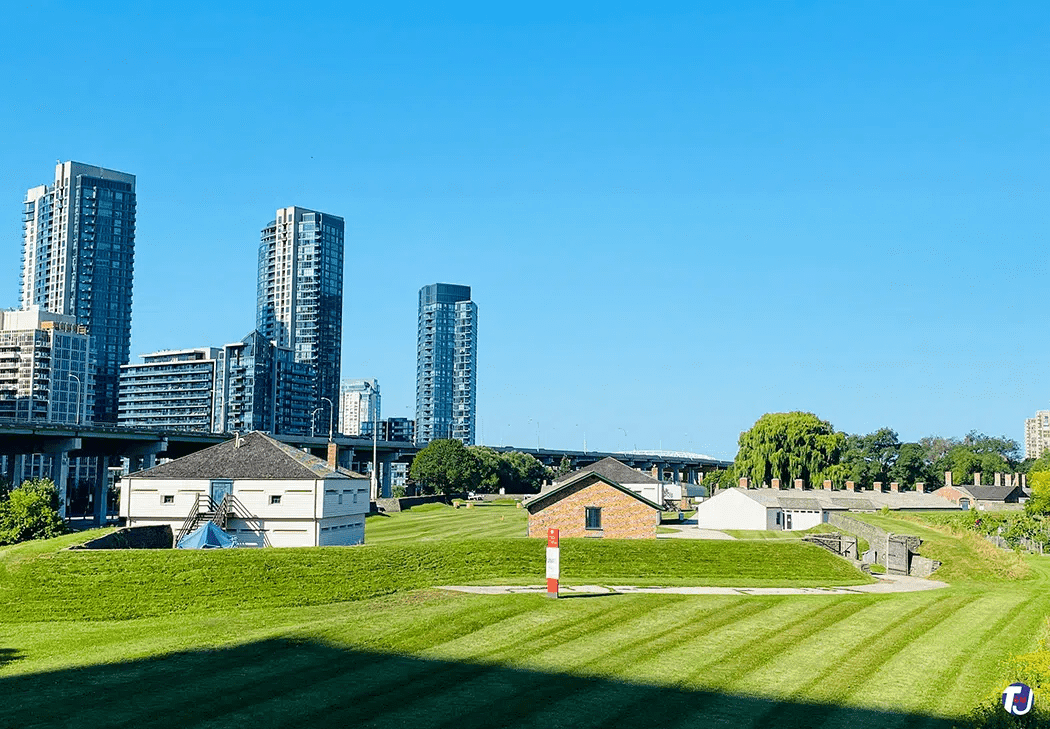

The National Historic Site of Fort York commemorates a series of British military installations that protected the entrance to Toronto’s harbour. Explore more about this significant site on toronto.name.

Overview of Fort York

The name “Fort York” is a retronym, as the fortifications were originally referred to as “The Garrison,” “The Garrison at York,” or “The Fort at York,” derived from the settlement it defended. York was twice raided by American forces during the War of 1812. In 1923, the 17-hectare area housing Fort York was designated a National Historic Site.

Construction began in 1793 to protect the harbour from enemy ships during wartime, featuring a stone powder magazine, wooden barracks, blockhouses, and earthen gun batteries. At the start of the War of 1812, York’s defences were relatively weak, despite the strategic importance of its shipyard in Toronto’s harbour. British forces believed York was too isolated and well-protected by their navy on Lake Ontario to be attacked by the Americans. However, by early spring of 1813, the American fleet gained dominance over Lake Ontario, allowing them to move freely without fear of British retaliation. On April 27, 1813, they launched an amphibious assault from Sackets Harbor, New York, aiming to capture British ships and naval supplies in York. Over 1,700 American troops, led by Brigadier General Zebulon Pike, defeated the British garrison of 300 regular soldiers, 500 militiamen, and 50 allied Indigenous fighters under Major General Roger Hale Sheaffe in the Battle of York.

American Seizure of the Fortified District

As American forces advanced toward the main British battery, Sheaffe ordered his troops to retreat, detonating the main powder magazine and setting fire to naval supplies and a ship under construction during their withdrawal. The explosion caused significant American casualties, including the death of General Pike. Following the British retreat, the Americans occupied York until May 8. Before departing, they burned government buildings, including Parliament’s facilities. In July, the American fleet returned and destroyed the remaining government structures.

When the British regained control of York, they began constructing new fortifications on the ruins of the previous site. By August 1814, the fort’s defences and artillery batteries had become strong enough to deter an American flotilla from entering the harbour. During the Upper Canada Rebellion, Fort York also served as a rallying point for local militia. Although the uprising was small, it prompted further construction in Toronto. By the early 1840s, the New Fort (later called Stanley Barracks) was built one kilometre west, housing a small British garrison until 1869. The Canadian militia continued to use both forts into the 20th century.

The powder magazine housed 74 tons of iron shells and 300 barrels of gunpowder. This contributed to a massive explosion that inflicted over 250 American casualties when the magazine was detonated during the British retreat. Fearing a counterattack after the blast, the Americans regrouped and delayed advancing on the abandoned fort until the British had left York.

Fort York: Past and Present

Development threatened Old Fort York at the turn of the 20th century, sparking public outcry over the potential loss of this Toronto heritage icon. In 1909, the Department of Militia and Defence transferred the property to the city under the condition that its historic buildings would be preserved. Restoration work was undertaken during the Great Depression, and “Old Fort York” reopened to the public in 1934 as part of Toronto’s centennial celebrations. Renamed Historic Fort York in the 1970s, this National Historic Site includes several original buildings, four of which date back to the War of 1812.

In fall 2014, a Visitor Centre was opened on the site, serving as the main entrance to the fortified district. Situated along what was once the Lake Ontario shoreline, the 2,400-square-metre facility includes exhibition, research, and community spaces. Designed by Patkau Architects from Vancouver and Kearns Mancini Architects from Toronto, the Centre cost approximately $25 million, including exhibit installations. The building’s southern façade is clad in weathered steel panels that reflect the historical bluff and shoreline location from the early 19th century. Since Toronto’s amalgamation in 1997, the fort’s museum operations have been managed by the city’s heritage service. In 2000, however, the city council transferred administration of the fort to a board of appointed citizens, separate from other municipal museums.

Notably, in September 2017, Fort York hosted archery events for the 2017 Invictus Games, a multi-sport competition for injured or ill military personnel.

The Reconstructed Fort (1813–1932)

In late 1813, plans were drafted to rebuild the settlement’s defences, including the fort and surrounding blockhouses, to protect a Royal Navy squadron of four ships intended for York’s harbour. Several structures were completed within the fort by November 1813, including the Government House Battery and Circular Battery, each equipped with two 8-inch mortars.

Blockhouses were designed to serve as barracks for the local garrison, ensuring troops could be stationed in the settlement as needed. In the following years, surrounding forests were cleared to deny American forces cover during a potential attack. Defensive earthworks, barracks, and the powder magazine were also reconstructed, although completion of the fort was delayed until 1815 due to a shortage of craftsmen. Progress was further hindered by the mild winter of 1813–1814, which disrupted the use of sledges for transporting supplies.

From late 1813 until the end of the war, Fort York functioned as a hospital centre, with the stationed naval squadron aiding in transporting wounded soldiers from the Niagara front to the settlement.On August 6, 1814, an American naval squadron arrived at York’s harbour, suspecting British ships were stationed there. The squadron dispatched the USS Lady of the Lake under a white flag to assess the city’s defences. However, militiamen stationed at the fort fired upon the vessel, prompting both sides to exchange fire before the Lady of the Lake withdrew to the squadron outside the harbour. The American fleet did not attempt another assault on the fort but remained outside York’s harbour for three days before departing the area.